FAQ

DIVE LAW FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Click the links below to read our questions and answers on the following topics:

MAINTENANCE PAYMENTS FOR THE INJURED COMMERCIAL DIVER

I’ve been hurt offshore and my company says all I’m entitled to is $35 per day for maintenance (maritime workers’ compensation), is this all I’m entitled to?

A diver injured in the service of a vessel is entitled to the maritime equivalent of worker’s compensation, more commonly known as maintenance, and payment of all medical treatment, more commonly known as cure. The right to receive maintenance and cure benefits is the most sacred legal right under Admiralty Law. A vessel owner must pay the seaman his full living expenses as he recuperates from an on-the-job injury.

Maintenance is defined as “financial resources by which the injured seaman can weather the financial storm surrounding an occupational injury offshore.” It also includes the expenses necessary to repatriate the seaman to his or her home. Maintenance includes the amount of money per day sufficient to defray the cost of food, lodging and utility expenses during his period of convalescence. Lodging expenses include expenses for rent, home mortgage and utilities.

Contrary to popular belief, a company may not arbitrarily choose payment, say $35 per day, and submit that it is satisfying its obligation under maritime law. If the maintenance payment fails to satisfy the diver’s daily living expenses, it is not only unfair to the diver, it is against the law.

JONES ACT BENEFITS VERSUS BENEFITS UNDER THE LONGSHORE AND HARBOR WORKER’S COMPENSATION ACT

I have been told that my claim falls under the Longshore and Harbor Worker’s Compensation Act, not the Jones Act. I always thought that all commercial divers are covered under the Jones Act.

What’s the difference between the two, and which law provides the greater remedy for a diver?

Most divers working from vessels are Jones Act seamen as a matter of law. As long as the diver is in the service of a vessel and is more or less connected to that vessel, or a fleet commonly owned, he is by law a Jones Act seaman. Some courts go so far as to proclaim that when a diver is working at depth he is “a vessel unto himself”. In those rare occasions where there is no vessel connection the diver is protected under the Longshore and Harbor Worker’s Compensation Act. In some states, such as Louisiana, the diver is a Jones Act seaman even if he dives from a platform or structure. The differences in benefits under each act are significant.

Perhaps the most widely recognized legislation in the area of maritime personal injury is the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, more commonly known as The Jones Act. The Jones Act provides that the employer of a diver is legally responsible for any damages sustained by an injured diver as a result of the negligence of the employer, a co-employee, or an agent of the employer. In brief, if a Jones Act employer, co-employee, or agent acts unreasonably (negligently) in its maritime activity and such action brings about harm to its diver, diving contractor must compensate the worker for all damages he sustained. Under the Jones Act the injured diver would be entitled to all of his past and future loss earnings and earning capacity, pain and suffering and any other proven damages.

Under the Longshore and Harbor Worker’s Compensation Act the injured diver is provided a stipend or allowance based upon 66.66% (2/3rds) of his annual average earnings, with a maximum of $1,047 and a minimum of $261.79 per week. The allowance is provided until the diver recovers or, in the event the injury is permanent, for a set number of weeks based upon tables provided by the U.S. Department of Labor. In addition to the compensation benefits the Longshore Act also provides that the worker is entitled to all costs for medical care and treatment as well as travel expenses to and from such treatment. Additionally, the worker is entitled to select the doctor of his or her choosing as long as the appropriate procedures are followed.

UNPAID MARITIME WAGES

I completed my work offshore on a vessel, it’s been two weeks and I have not received my pay check. I just can’t get my paycheck.

What are my legal rights?

The law with respect to failure to pay seaman’s wages is very clear and provides significant penalties under Federal Maritime Law.

Under the Federal maritime Law the Penalty Wage Statute provides;

At the end of a voyage, the master shall pay each seaman the balance of the wages due the seaman within 24 hours after the cargo has been discharges or within 4 days after the seaman is discharged, whichever is earlier.

When payment is not made as provided without sufficient cause, that master or owner shall pay to the seaman two days’ wages for each day payment is delayed.

Should the seaman not be paid there exists a maritime lien on the vessel. This lien primes any other lien, including a vessel mortgage.

How does the law define “without sufficient cause”?

The only way a master or owner can avoid payment is if the owner is insolvent and financially can not pay the seaman.

If the seaman is not paid within the times mandated by law the burden shifts to the vessel owner to prove that the owner was unable to pay the seamen.

Obviously, this Federal Law gives the seaman a strong tool at his disposal to seek the enforcement of this longstanding legal right.

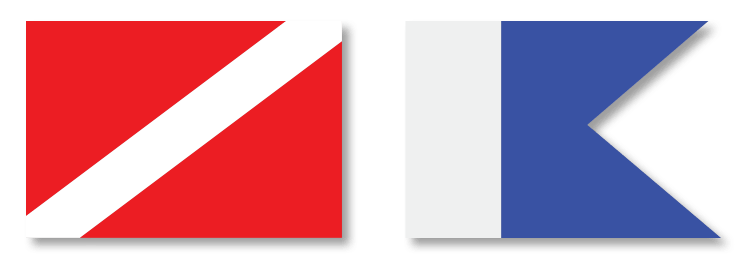

THE INJURED DIVER’S POST ACCIDENT CHECK LIST

I was just injured in a diving accident while working offshore. What should I do?

First of all, don’t panic. The maritime law was written to protect your legal rights in time of peril. The Jones Act was written to provide mariners with more legal rights than land based workers in an attempt to encourage young men and women to enter the maritime work force. If you are a mariner, the law is on your side.

Most importantly, first find the finest in medical support, advice and counsel. Locate a qualified hyperbaric medical doctor, closely follow his/her advice and allow your doctor to all of your medical treatment.

Under maritime law an injured diver is entitled to his choice of medical providers; and, the diving contractor remains obligated to pay for the diver’s medical expenses, his travel to and from the health care provider and medical facility, and lodging should the diver reside out of town.

Documentation of the dive profile, decompression, recompression and on-site medical treatment is important. Secure and copy the dive log, field neurological exams, vessel logs and any other document which could establish the dive profile, decompression, recompression and treatment. If possible get a copy of the accident report or witness statements.

Prior to seeing your doctor sit with your wife/husband, girlfriend/boyfriend or family member, and make notes of your complaints. Write down any questions you may have for your doctor. Your doctor is busy and in a hurry; you are nervous or your memory isn’t what it should be. Having notes helps. If you are concerned that your doctor is not closely listening to your complaints give him a copy of your notes.

If possible avoid giving an oral or written statement until you have consulted with an attorney. There is no need to immediately hire an attorney; speaking with one may prove valuable at a later date. Be suspicious of someone who tells you that you must give a statement before the company can begin maintenance payments. Such is not the law.

Maintain a personal log of the events which have occurred following your return to shore. Chronicle your doctor visits, medical examination and procedures. The medical specialist you see will want to know as much as possible about your history. Keep a log; it’s better than your memory.

Retrieve all of your medical records including medical reports from your treating physician and specialists. The insurance company adjuster and your company safety officer will have access to your medical records. Shouldn’t you?

At times it will seem that everyone has advice to give you. It’s foolish to take medical advice from anyone other than a diving doctor; that includes your company representative, your buddy, your family or your spouse or significant other. It’s foolish to take legal advice from anyone other than a maritime lawyer familiar with diving; that includes your company representative, your buddy, your family or your spouse or significant other. While everyone wants to give advice to the injured diver, only the injured diver has to pay the consequences of poor advice.

Finally, don’t be rushed to make any decision until you are confident that you have most, if not all your concerns and questions addressed. Don’t be rushed to settle your claim, hire an attorney or go back offshore until you are fully ready to do so. It’s your career, no one else’s.

THE PATENT FORAMEN OVALE ISSUE

Recently I was bent following a questionable dive. I went to a diving doctor who suggested I get a test to determine if I have a PFO (Patent Foramen Ovale). We found out I have a PFO and my doctor disqualified me from diving. My company said they are not responsible because a PFO is a congenital defect. My career is lost. What should I do? Do I even have a legal remedy? I’m lost

Next to questions concerning maintenance payments the above questions about the PFO are the most frequently asked questions we hear at Delise and Hall. Questions concerning the effect of PFO’s on the working diver are also widely debated in the hyperbaric medical community.

There are no easy answers to this legal-medical quandary. Here, however, are the salient issues of which all working divers should be made aware.

Here is a very basic overview of the medical-legal issue of patent foramen ovale in divers.

The foramen ovale is a passage or opening between chambers in the heart that allows blood from the inferior vena cava to freely enter the left atrium while a baby is in her/his mother’s womb. A patent foramen ovale (PFO) occurs when the passage does not fully close as an individual ages. This condition is found in approximately 1 out of every 3 humans.

Where this becomes an issue for commercial divers – statistically one out of every three commercial divers – is when the shunt is large enough to present the possibility of shunting of gases from the venous to the atrium chamber while a diver is off gassing or when the diver engages in a valsalva maneuver. The gas enriched blood goes to the atrial side of the circulatory system and there is a greater possibility that the diver gets bent or suffers arterial gas embolism.

That’s a very crude and basic explanation.

Where the issue of PFO’s comes into play in the commercial diving industry is when a diver is diagnosed as having a PFO, a finding that can result in serious consequences for a diver’s career. If the PFO is discovered following an incident of CNS or AGE, a doctor may disqualify a diver permanently if the PFO is large enough, can’t be repaired or if the reason the doctor believes the CNS incident occurred was because of the POF and/or if the doctor believed the CNS incident was an undeserved hit. An “undeserved” hit may be a hit where all the tables were followed perfectly, the diver was well rested and there is no other reasonable explanation as to why the diver got bent. In such cases the reason for disqualifying the diver isn’t because he was bent because of anything happened during or after the dive, it’s because the diver had a PFO. Sorry, you’re permanently disqualified and there’s very little that can be done about it.

There is an operation to close the PFO, however, and it is beginning to be well received by the medical community. But, it’s heart surgery, and the jury is still out over whether it will be well received by the divers.

If a PFO is disqualifying, and remember that one in three divers have a PFO, the obvious question becomes: “why isn’t it part of the medical screening prior to entry in dive school?” And, “if this is such a big deal why aren’t divers screened annually or as part of the annual ADCI physical?” These are important questions that no one in the dive industry can, with great clarity, provide an answer.

In many instances where a diver is bent the company and/or the treating doctor requests that the diver undergo the testing to determine whether he has a PFO. It’s the appropriate and wise advice. However, some insurance companies often use this controversy to seek to deny Jones Act claims where the diver gets bent. If the diver has a PFO it is argued that the diver was bent, not because the company made a mistake, but because of the diver’s PFO. Again, if one in three divers has a PFO it’s a big deal when someone gets bent.

We at Delise and Hall have always argued if the presence of a PFO in a commercial diver is so important then perhaps screening, pre-bents injury, is important. Also, it’s a specious argument for a company to try and escape liability if the CNS is the result of something OTHER THAN THE PFO, such as the rate of ascent was bad, the diver was “z’ed”, the table wasn’t followed, or the ADCI rest period mandates were ignored. There are many reasons a diver gets bent, reasons which HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH THE PFO.

Our argument is especially persuasive if the diver has dived hundreds of dives WITH A PFO, and it was only when there were mistakes made that the diver got bent!!!!!!!!!!!

Simply having a PFO does not give you a right to file suit against your company. But if you have a PFO, it’s probably because you learned you had it after an incident. The question then becomes “why did you get bent?” If it’s because it was the fault of the company, equipment or poor decisions by those running or planning your dive, or it’s because of improper decompression or recompression therapy post onset of symptoms, the issue of the PFO becomes less meaningful and, in some cases, totally irrelevant.

If any one has more specific questions about this matter simply contact us and we’ll do our best to describe the legal controversy. If you have medical questions we can help point you in the right direction to get medical advice on this very important, confusing and rarely discussed medical-legal issue.

HIRING AN ATTORNEY

How do I know when I need to hire an attorney? How do I select a good one?

In brief, one should consider hiring an attorney when the diver feels so uncomfortable that he believes he is entering “un-chartered waters”, so unfamiliar to him that he is getting very anxious about securing his rights under maritime law. It is also suggested that a diver not hire an attorney unless he has a career threatening injury. Be confident in knowing that all information shared in conversations with an attorney is confidential. The attorney is duty bound by law not to disclose in any consultation even if the diver never retains the services of the attorney. Consider the conversations “safe harbor”.

Simply speaking with an attorney does not commit the diver to instituting litigation and suing his employer. Consulting an attorney simply provides the diver with the fundamental tools needed to make an informed decision.

While we do not suggest hiring an attorney unless the diver’s career is in peril, it is highly recommended that a diver consult an attorney if he feels he is in need of advice and counsel to make rational decisions.

The process of hiring legal counsel is often as traumatic as talking with an adjuster or an insurance company representative. It should not be so as long as one keeps in mind that hiring an attorney is just that – one hires an attorney much like hiring an employee. The attorney works for the client, not vice versa. An attorney – client relationship does not exist unless the attorney and client formally enter a written agreement formalizing the agreement. Additionally, the agreement should specify the terms of the agreement. The terms may be based on a contingency or hourly agreement; the agreement should also specify how the expenses are to be repaid.

In hiring legal counsel be sure that the attorney is well qualified in the field of maritime law and the intricacies of diving physiology and diving physics. It is dangerous to hire an attorney who gains his or her knowledge of diving during the prosecution of the lawsuit at the diver’s expense. Some attorneys don’t know the difference between a SUR O2 table and a coffee table. Ask the attorney poignant diving related questions. In hiring an attorney one must have the same faith or trust in one’s attorney as he had in his tender or supervisor. Much of one’s future will be in the hands of the attorney. In hiring an attorney investigate his qualifications. You can learn quite a bit about an attorney from his past clients.

Be aware of the rules that govern the conduct of attorneys. It is a felony in some states, such as Louisiana, for an attorney to pay individuals or “runners” money or “finder’s fees” for getting a diver to hire an attorney. If an attorney will “buy the case” he will most certainly “sell the case”. Bar association and state law govern how attorneys can assist a client with living expenses paid through “client advances” on the case. In some states an attorney may be disciplined, or even disbarred, for promising money to get the case or keep the case. The last thing an injured diver wants is for his attorney to be disbarred in the middle of his case.

If there are questions about the conduct of an attorney simply call the Bar Association where the attorney practices.

A GIRLFRIEND’S LEGAL RIGHT TO FILE SUIT IF HER BOYFRIEND DIES WHETHER THE DIVER WAS KILLED WHILE WORKING OFFSHORE OR IN A NON-WORK RELATED DIVING ACCIDENT

My boyfriend and I have been living together for years. We are not married though we do have a child together. Do I have any legal rights if my boyfriend dies; and if not, who has the right to sue the diving company or private entity that caused his death?

The only situation where the girlfriend of a deceased diver is entitled pursue a legal claim for her personal damages and loss of financial support occurs when the couple was domiciled in a state which recognizes “common law marriages” prior to his death. In those states which do not recognize common law marriages, such as Louisiana, the girlfriend has no right to pursue a legal claim. If the couple had a child together the mother may present the child’s claim as the child’s legal representative. If the diver leaves no children all of the rights to pursue the diver’s claim or the family member’s claims go the “family” of the diver, starting with the parents.

CLAIMS FOR INJURIES/DEATH OCCURRING OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES

I am a recreational diver injured outside of the United States, can I still bring a claim?

Americans injured or killed abroad do have the right to pursue their legal claim. In most instances involving injury the case is governed by the general maritime law which allows the injured parties to recover for their past and future medical expenses, past and future lost wages and for their pain and suffering. Often these claims can be brought in the United States where either the injured party lives or the defendant has sufficient contacts.

In order to be successful in pursuing the claim in the United States it is imperative that legal counsel uncover, establish and document that the wrongdoer has a connection to commerce in the United States. Establishing such a connection requires that legal counsel investigate the facts and circumstances of the incident as soon as possible prior to the wrongdoer’s altering his relationships in the United States.

Most maritime deaths such as a scuba diving accident are controlled by the Death on the High Seas Act, a federal statute that allows relatives or dependents killed in foreign waters to bring a claim in federal court in the United States.

MARITIME STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS

I was injured offshore in a diving accident at work (or at play). How long do I have to bring my claim?

Most maritime actions, including injury or death, are governed by a three year statue of limitations meaning that suit must be filed within three years of the date of the accident. Waiting the full three year period to file a suit may be a very risky decision. In most cases finding the proper party may be a difficult and time consuming problem. Over time witnesses lose their memories, disappear or die. Over time key evidence is lost, destroyed or spoils. Companies go bankrupt.

In diver death cases unless a medical examiner proficient in conducting a proper diving autopsy is used there is the possibility that the proper “medical cause of death” will not be established. In-water deaths are often inappropriately classified as heart attacks or drowning when if fact an air embolism, decompression illness, or breathing contaminated air or improper breathing mixture, is the true “cause of death”.

Even if an injured diver or his surviving family decides to delay instituting litigation until the last minute it is imperative that a skilled investigator or legal counsel initiate a professional investigation as soon as possible.

SIMPLY FINDING OUT WHAT REALLY HAPPENED

I don’t think I want to file a lawsuit. I just want to know what happened.

Very rarely is a thorough investigation done by local authorities following a diver fatality. This is especially so when the incident occurs abroad. In many instances, evidence is lost purposefully and witness identification is not made. In such cases familiarization in dealing with foreign embassies, officials and coroners is required. Only experienced maritime attorneys should be used in connection with the initial investigation of the diver’s death.

Soon after the death occurs it is necessary that a professional medical examiner be called, arrangements be made to deliver the body to the proper authorities and all key diving gear is located and preserved. If the diver used a dive computer it must be recovered. Statements of the diver’s buddy and family members should be taken. If possible a survey of the dive site should be conducted. Sometimes a lawsuit is not warranted, but ascertainment of the truth can only begin after a thorough professional investigation by those skilled in diving procedures and maritime law.

BREAKING LIABILITY RELEASES (WAIVERS)

I signed a liability release prior to my accident, can I still file a lawsuit?

Some states strictly enforce release agreements, also known as waivers; other states hold them void and unenforceable. Each state has its own rules. Even if an injured diver resides or was injured within a jurisdiction that enforces release agreements there may be several exceptions that apply to still allow the diver, or his surviving family, to file a lawsuit. For example, most states will not enforce a release agreement where it is shown that the negligent party acted in a willful or wanton manner or was grossly negligent. Releases involving minors are often unenforceable. There are many other exceptions that may apply. It is important to review the actual language of any agreement as well as the circumstances under which it was signed. Many divers have signed releases prior to their accident and have successfully pursued a claim. Determining whether a waiver is valid requires a learned legal review of the specific facts of the execution of the document and the circumstances of the dive at issue.

FINDING A QUALIFIED DIVING DOCTOR

My treating physician is not familiar with diving (hyperbaric) accidents. Where can I go for treatment?

We at Delise and Hall are not doctors. However, we have developed long standing relationships with the top hyperbaric experts in the world and often give seminars to physicians regarding the legal aspects of diving medicine. We are often able to assist in coordinating medical care for our clients to help insure adequate, informed health care provided by physicians who have the qualifications to render medical care and assistance to the injured diver. Need to find a diving doctor in your area? Give us a call.

THE LEGAL RIGHTS OF A PUBLIC SAFETY DIVER

I am a fireman injured during public safety diving training. Do I have the right to bring a claim?

An injured public safety diver, or his surviving family, in most cases has a viable legal claim against his/her employer under a state workman compensation statute. Additionally, the diver or his family may have a claim against the instructor and his certifying agency who “qualified” the diver as a “public safety diver”.

NON-DIVING MARITIME CLAIMS

I was injured while on a jet ski, parasail or while swimming can Delise and Hall still help me?

The same principles govern most aquatic and recreational injuries (and death claims). Delise and Hall has successfully represented clients in a variety of aquatic activities which have resulted in serious or fatal consequences; these include incidents involving personal water craft, boating collisions, propeller injuries and swimming accidents, etc. If you are injured in a maritime setting Delise and Hall can assist you.

TECHNICAL DIVING CASES

I suffered decompression sickness while making a technical dive to 335′ on trimix. I was not taking a class and have a lot of diving experience. Do I have a legal right to make a claim?

Experienced technical divers have the expertise, skill and training to go where very few humans dare to venture. The equipment used by the technical diving community is complex though based on reliable science. Training agencies have at their disposal cutting edge techniques in supporting the experienced recreational diver’s leap into the world of technical diving. Or so the theory goes.

We at Delise and Hall are not only attorneys well versed in admiralty law; we are also experienced technical divers. Our diving logs show that we have made hundreds of cave, wreck penetration and deep dives. If an injury or death has occurred and the cause of the incident is unknown we will get to the bottom of it. If the cause of the injury or death is the result of improper or deficient training, malfunctioning dive gear or negligent medical certification or treatment we will uncover the evidence to support a legal claim against the responsible party.

We will personally dive the site and complete a thorough survey utilizing video documentation. We will personally inspect the equipment and if necessary engage the best experts to answer the highly technical questions associated with decompression, gas mixes and technical training injuries and deaths as well as those not involving training in which there was negligence on the part of boat personnel or those directing the dive or providing first aid. Malfunctioning equipment such as computers or gas mixtures are also sometimes to blame.