COMMERCIAL DIVER DEATH

DIVER KEEL-HAULED BELOW SUPERTANKER

Root Causes of Incident:

- Inexperienced Exhausted Supervisor

- Exhausted Crew

- No JSA’s Used or Followed

- No Rescue Plan

Commercial diver, MS, age 28, was killed when he was pulled underneath a supertanker being cleaned off the coast of Galveston as he was attempting to return to the dive vessel following a helmet malfunction.

Bobby Delise and Alton Hall of Delise and Hall were asked to represent the diver’s widow and the diver’s three surviving children, ages 2, 4 and 9. The case was filed in the United States Federal Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana.

FACTS

Dive Project

Several months prior to the death of the diver a GOM diving contractor, not manned, equipped or experienced in ship husbandry, decided to open a ship husbandry division through its subsidiary. This special division would act a mobile “SWAT team” of divers, supervisors and support crew to travel on short notice to clean ships in a geographical swath from the East Coast to the West Coast.

Shortly after the subsidiary’s formation the diving company contracted with a foreign vessel’s agent to clean the hull of a supertanker moored off the coast of Galveston. At the time of his death the diving contractor directly employed MS.

From the onset of the project the job the diving contractor’s effort to complete the project was an abysmal failure. After working for 27 hours straight, giving the crew of divers and tenders no rest, the on-site diving supervisor advised his superiors onshore and the captain of the supertanker that he had to suspend operations and return to harbor to secure more experienced and rested divers. A call was made for more divers and MS was sent offshore.

On the morning of MS’s death the diving contractor was faced with the task of completing the scouring of approximately 40% of the hull of the supertanker. The company, because of its inept planning, was severely behind schedule and matters would only worsen as the day progressed.

Date of Diver’s Death

On the date of the diver’s death diving operations commenced at 05:24 with Dive #1, a dive that was aborted because of a malfunction in the diver’s helmet. During dive #2 some work was completed but it too was aborted because of equipment failure. Dive #3 was short in nature with very little work being completed.

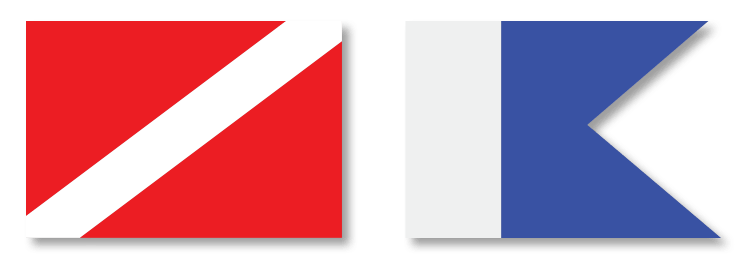

MS’s dive – the dive when he was killed - was scheduled to last 200 minutes at a depth ranging from 30-40 feet below the surface as he guided the hydraulically powered dual head rotary device along the hull of the supertanker. All of the images seen by MS were contemporaneously transmitted via a helmet camera video feed to a video monitor in the dive shack. All audio communications were transmitted by radio link to the supervisor. The dive was recorded by the company’s DVR within the dive shack to confirm to the owner of the supertanker that the work done.

MS’s dive commenced at 09:34. On the radio running the dive was the diving contractor’s supervisor. A standby diver was designated, as were two tenders - one tending the diver’s umbilical, one tending the rotary scrubber’s hydraulic hose.

At the time of the project the DSV was positioned and moored the supertanker’s port side. MS had for 2 hours guided the rotary device along the port side hull and the flat bottom of the vessel. At approximately 120 minutes into his planned 200-minute dive a loud shrieking squeal is heard over the comms in the dive shack. This is a clear indicator of problems with air supply to a diver. Diver MS immediately pled “up and out on diver”. In reply to MS comment ‘up and out on diver’, the supervisor responded, “say again?” to which MS again reported “up and out on diver”. The supervisor confirmed his acknowledgement in replying “up and out on diver”; the supervisor then reported “coming up on you” apparently believing that MS was on the port side of the supertanker.

Within 22 seconds following the supervisor’s “coming upon on you” MS is seen surfacing on the video monitor on the starboard side of the vessel. MS was on the opposite side of the vessel from the dive vessel.

Immediately upon surfacing MS reports, “all right I’m having an issue with my air”. The DVD of the dive very clearly confirmed that on the monitor that the diver made three breaths and then mysteriously the audio feed disappears.

For a period of 90 seconds the video shows MS on the surface calmly treading water. Over that time period MS pivots 180 degrees and then begins slowly swimming toward the bow of the supertanker, he stops and reaches below the water to twice grab his umbilical. He lifts is head above surface and continues to tread water. It is then clear seen that MS then removes his dive helmet.

A close review of the video reveals that after removing his helmet MS remained next to the hull of the supertanker for an additional one minute. In response to what he sees the supervisor then panics and tells the tender to go “wake everyone up” as the diver removed his helmet. In response an awakened tender on surface panicked and pulls MS umbilical “keel-hauling” him to his death. A close viewing of the video shows MS convulsing on bottom. He remained on bottom for several minutes until the standby diver comes to his side and brings him to surface. Once on surface CPR is attempted to no avail.

HOW AND WHY DID THIS TRAGEDY OCCUR?

The designated tender, testified in sworn testimony that at the time of his diver reporting his problem, the tender was in the dive shack “with my eyes closed”, positioned away from his post on deck and yards from where he should have been tending MS’s umbilical. Upon his “seeing the diver taking his helmet off”, he testified that he was told by supervisor to “go wake up everyone” to assist help with the emergency.

One tender testified that he woke up the other tender who was behind the dive shack, apparently asleep; the secondary tender, upon hearing the excitement, ran and grabbed the umbilical and pulled it “double fast” until MS finally surfaced minutes later dead. This tender stunned, in a sleep induced stupor, was apparently unaware that prior to his “keel hauling” MS that the diver was on surface, helmetless and breathing the fresh salty air.

DELISE AND HALL’S REPRESENTATION OF THE DIVER’S FAMILY

Delise and Hall argued that MS died as follows. At 120 minutes into the planned 200-minute dive MS reported some type of problem with his helmet and/or air supply following a squealing sound from his helmet, which is clear indication of an air delivery problem. He surfaced and reported the problems clearly. Faced with the realization that staying in a helmet, which isn’t supplying him air he made the decision anyone would make under the circumstances. He removed his helmet to take in all of the fresh air that the world supplies.

The diving supervisor, inexperienced and exhausted, and who was quickly promoted two weeks earlier to fill the need of the husbandry SWAT team, panicked and ordered his tenders to “come up on the diver” believing he was on the port side of the supertanker. Delise and Hall argued that had the tenders been tendering his hose properly they would have known that MS was on the starboard side of the vessel.

Delise and Hall summarized its argument that the diving contractor was at fault because of its failure, through it’s on site supervisory personnel, to prepare a plan to complete the task at hand.

Delise and Hall also argued that the diving contractor failed to provide its crew proper rest and the training to complete the task at hand and were in direct violation of the ADCI minimum rest policies and procedures.

The diving contractor utilizes federally mandated safe practices manual. Included within the manual are requirements focusing on pre-project planning procedures, which include implementation of “safe actions plans” and formalized written Job Safety Analysis forms (JSA), specifically prepared for each project.

In this case the diving contractor grossly failed to prepare any such plans or JSA’s. In response to questions concerning what was told to the supervisor about the safe action plan the diving supervisor arrogantly replied under oath: “what is the plan? The plan is to go there, do the job and do it safely . . . the plan is to go there and clean the hull”. In response to a request for the JSA in place on the day of the incident the diving contractor’s representative could only produce a generic document having nothing to do with the work required.

Delise and Hall argued successfully that the diving contractor fell woefully short in planning for the manning requirements of the project. For the two days prior to MS’s death the diving contractor failed to adhere to the ADCI (Association of Diving Contractors International) minimum rest period requirements. On the day before MS’s death a Facebook entry by the diver’s tender posted that he was so tired on the job that he is “delusional”. Evidence will show that both tenders were either asleep or “with eyes closed” when the emergency occurred. Faced with MS’s emergency the exhausted crew responded in a confused disordered manner. They panicked clear and simple and the result proved fatal to MS.

Lastly, the diving contractor’s supervisors failed to put in place a plan to rescue a diver faced with MS’s peril.

In short, this was a project that was destined to kill a diver. The supervisor was inexperienced, the company was ill prepared to conduct such a project and its crew was overworked, under trained and incapable of dealing with an emergency.

RESOLUTION

Delise and Hall convinced the diving contractor’s insurance carrier to resolve the case during private mediation within one year of the death of MS. Because of the serious of the settlement terms the amount of resolution paid to MS’s family is confidential.