HURRICANE SAFETY: YOUR RIGHTS AS A MARITIME WORKER AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF EMPLOYERS

HURRICANE SAFETY FOR OFFSHORE WORKERS AND DIVERS

Riding out a hurricane several miles on land is a frightening experience for the most stalwart among us. Riding out a hurricane offshore defies description. Only the most blessed live to tell the story.

Mariners across the Gulf Coast have recently experienced more storms than the “old-timers” can recall. Unfortunately, the recent storms have claimed far too many maritime casualties related to improper emergency evacuations.

This short article will address the following question which has been posed to Delise and Hall quite a bit of late: what is the legal responsibility of a maritime employer or vessel owner to evacuate their employees or passengers as a hurricane approaches?

DUTY TO PROTECT

Unlike land-based worksites the offshore environment presents several unique challenges for the maritime worker. “Commuting” to a mariner’s workplace involves not only exposure to the “perils of the sea” and but a strict reliance on others for transportation to and from oilfield platforms, drilling rigs or “on location”.

Under the admiralty law a maritime employer of “seamen” must exercise reasonable care in the evacuation of its personnel during hurricane season or times of perilous weather. The employer must take all reasonable precautions in securing information concerning approaching weather, potential effects of the storm and the timeline for the storm’s arrival. Once it becomes probable that the storm’s fury will present a risk of harm to its personnel the employer is duty bound to provide safe and secure evacuation to safe harbor. Under the law the “duty to protect” life primes any concern, including the value of equipment or job completion.

Likewise, a maritime contractor in the business of transporting personnel to and from offshore facilities or work sites must do everything in its power to ensure that the voyage is conducted in the safest manner possible. The vessel owner must ensure that its crew is competent and that its vessel is fit.

Federal agencies have enacted statutory mandates to protect offshore workers threatened by severe weather in the Gulf of Mexico. A most important mandate is the requirement to enact and publish an Emergency Evacuation Plan.

EMERGENCY EVACUATION PLAN

In reviewing the actions of an employer in protecting the lives of its employers during hurricane or severe weather evacuation one first inquires as to whether the company published a severe weather guide or an emergency evacuation plan, also known as an “EEP”. A properly drafted EEP specifies detailed actions necessary to prevent risk to personnel and equipment in the storm’s path.

The plan should provide specific action plans once the storm passes predetermined radius milestones from the work site. Among an almost endless list of exigencies within the “action plans”, the company should identify transportation needs for “essential” and “non-essential” personnel. Action plans for vessels should spell out when “evasive” action, rather than “flight to safe harbor’”, should be initiated. No plan can be too detailed.

Having an EEP is only the first step in protecting personnel from the wrath of an approaching storm. Practicing, perfecting and implementing the plan come next. Companies should practice implementing the plan until it becomes second nature. And, as we’ve seen in recent storms, failure to “follow through” with the EEP can be as dangerous as having no plan at all.

TWO LANDMARK ADMIRALTY CASES

As stated above, under statutory and admiralty law a maritime contractor working in the Gulf of Mexico is obligated to prepare and execute when storms threaten. Failure to fulfill this obligation exposes the delinquent company to damages should an employee or someone under their care sustains damages.

Two landmark maritime cases illustrate how companies who fail in their obligations to follow their EEP pay the price.

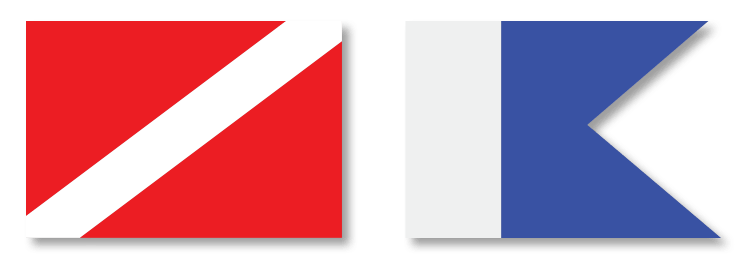

In 1995 a major diving contractor failed to evacuate a dive crew from a derrick lay barge working in the Bay of Campeche in anticipation of Hurricane Roxanne. As the storm approached the vessel began to sink. While in tow the divers abandoned ship and jumped into the 30-35 foot seas. One of the divers filed suit and a judge trial convened in southern Louisiana.

In 2000 the court concluded that the diving contractor was negligent, in part, for failing to evacuate its dive crew from the barge in anticipation of Hurricane Roxanne’s arrival, in failing to order the barge’s tow to safe harbor and failure to execute the company’s EEP.

In a similar scenario another admiralty court reviewed the actions of a vessel in its evacuation of employees from a drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico during Hurricane Danny in 1997. As the storm approached oil company representative decided, in adherence to its EEP, to evacuate 25 non-essential workers from the rig. The oil company contacted its charter vessel dispatching it to the rig to evacuate the workers.

The vessel arrived, picked up the worker and headed for safe harbor. Unfortunately, the vessel’s captain either failed to monitor the path of the hurricane or didn’t heed the National Weather Service’s report that the hurricane had turned sharply into the vessel’s course. The vessel encountered violent seas, heavy rains and rough seas. The vessel was blown off course and ran aground on a sand bar. The captain freed the crew boat and set out for deeper water to wait it out. Two workers sustained injuries in the 15 hour voyage, which under normal circumstances should have taken no more than 6 hours.

The admiralty court concluded that the vessel’s captain breached his duty to take reasonable care of the passengers aboard the vessel. The seminal mistake of the captain, the court concluded, was his failure to monitor the weather updates and adjust his course accordingly.

THE BOTTOM LINE

On even the calmest days offshore, the maritime workplace exposes the professional mariner to what is termed in Admiralty Law, the “perils of the seas”. When Mother Nature unleashes her fury offshore the mariner is dependent on others to see him to safe harbor. The admiralty law recognizes the obligation of an employer or vessel owner to not only recognize the this obligation but also to prepare to evacuate those under their care in a safe and professional manner.